By Jam Magdaleno and Cesar Ilao III

RECENTLY, the proposed Parents Welfare Bill surfaced in Congress. This bill seeks to “further strengthen filial responsibility and to make it a criminal offense in case of flagrant violation thereof.” Unsurprisingly, it has triggered fiery debates and vitriol online. The idea of punishing children who fail to support their aging parents touches a cultural nerve. But while much has already been said, the discourse generated by the proposal functions more as a political distraction.

It frames the issue almost entirely as a matter of moral responsibility, raising the wrong questions while ignoring a simple truth: it’s our protectionist economy that condemns many Filipinos to undignified aging. This, precisely, is what (dis)incentivizes filial piety.

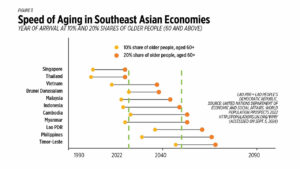

What the debate overlooks is a more honest reckoning with long-term demographic projections and structural realities. Two weeks before the bill went viral, the World Bank released a timely report on the demographic and poverty trends among older Filipinos. Current projections estimate that by 2029 and 2066, older Filipinos aged 60 years and over will comprise 10% and 20% of the total population, respectively. These findings are aligned with the Commission on Population and Development’s projection last year that the country will become an “aging population” by 2030. This means that while the population continues to grow — albeit more slowly — the count of older people is increasing.

The World Bank report classified the Philippines as an early-transition economy. This means that it continues to demonstrate rapid population growth and boasts a high number of young people. But the crisis is already here, we’re already facing the challenges of an aging population. Many retirees are living with meager or non-existent savings and pension payouts, forcing them to rely on their children for financial support and skyrocketing healthcare expenses.

The report comes with a stark warning: If not addressed, demographic transition marked by an increasing population of older people can place a significant strain on an economy’s fiscal resources.

And this is the elephant in the room: It’s not simply that parents’ children or the State refuse to neglect elders. Both public and private pockets are running empty.

On the State’s side, the country’s social protection institutions are struggling. The Social Security System (SSS) is projected to be shaky starting 2039, as benefit payouts begin to outpace contributions due to worsening worker-to-pensioner ratios. Currently at six contributors per pensioner, the ratio will fall to 3:1 within two decades. The core issue is under-contribution: you have too few workers, paying too little, into a fund meant to support too many. While the P700-billion reserve fund remains stable in the short term, it’s projected to be depleted by 2054, after which the SSS will carry a P4-trillion unfunded liability, leaving it unable to fully pay future benefits.

The Government Service Insurance System (GSIS), which serves public-sector workers, is in relatively better shape. Its fund life is projected to last until 2058, bolstered by consistent employer contributions, mandatory coverage, and a smaller pool of retirees. However, GSIS covers only 2.7 million members who are mostly permanent government employees, a fraction of the country’s total workforce. The GSIS model is only stable because its membership is small, formal, and backed by the state’s taxing power.

On the side of Filipino children — those meant to share the legal and moral duty — the challenges are equally severe. Four in 10 Filipino workers are part of the informal economy, which means exclusion from regular pensions and health insurance. Even formal workers are burdened by the rising cost of living. Many belong to the so-called “sandwich generation,” caring for both their children and their aging parents, while trying to build their own future. What’s more, a single hospitalization in a private facility can cost anywhere from P250,000 to over P1,000,000, depending on the critical care availed, far exceeding the approximately P227,000 average annual income per capita.

The current debate distracts us from asking the relevant questions. Why does the state lack money for social services? Because its economy is too feeble to generate enough taxes and contributions. Why is the economy weak? Because we block investments, restrict trade, and stifle industries instead of opening them. This isn’t just cultural neglect, but economic failure. We failed to design an economy that makes aging secure and dignified.

But our young population remains a silver lining. Our demographic window gives us a rare chance to act early. Unlike its neighbors, already in later-transition stages of demographic shift, the Philippines can still build an inclusive system for aging.

Why does this matter? Having a young population means two things: One, more people can work and earn. Two, younger citizens generally mean fewer medical needs, keeping healthcare costs down and the system more manageable. But this opportunity comes with a caveat. A young population can only become an asset if it’s empowered to work productively. This means creating high-quality jobs, attracting more investment, improving the business climate, and strengthening education. When workers thrive, the State collects more taxes and contributions. Those collections fund public services, including hospitalization, elderly care centers, and pensions.

The path forward must be two-pronged.

First, we need to raise real disposable income. This means ensuring that Filipino families earn more and spend less on basic needs. One way is by attracting higher-quality, better-paying jobs through economic openness. Despite reforms in recent years, the Philippines lags behind its ASEAN neighbors in investment: foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows to the country were only $9.2 billion in 2023, compared to $20.2 billion for Vietnam and $22.4 billion for Indonesia. Further liberalizing our investment climate, expanding the coverage of free trade agreements (FTAs), and removing constitutional restrictions on foreign participation are essential for economic dynamism and job creation. This will result in more formality in the labor market, as higher-value industries absorb workers and incentivize compliance with labor regulations. Formal employment means that workers are included in the pension system and have access to health insurance, social security, and stable wages.

We also need to address the high cost of living, especially food. The Philippines has among the highest food inflation rates in Southeast Asia. In 2023, food inflation peaked at 11.2%, disproportionately affecting poor and lower-middle-income families. Lowering agricultural input prices — especially for corn, which directly affects feed and meat prices — through deregulation and reduced tariffs will help stabilize food costs. Encouraging land consolidation for economies of scale and investing in rural infrastructure will also improve farm productivity and lower food prices.

At the same time, open-access reforms in sectors like telecommunications and transportation are long overdue. Filipinos pay some of the highest internet costs per Mbps in the region, limiting access to online learning and e-commerce. Liberalizing these sectors and improving infrastructure will reduce consumer costs and make services more inclusive.

Investments in education and upskilling are equally vital. As of 2022, one in five Filipino youths aged 15 to 24 was not in education, employment, or training (NEET). Strengthening vocational education, supporting industry-academe linkages, and implementing voucher-based systems for skills training can help equip the young labor force to meet future economic demands.

Second, we must sustain greater funding for social infrastructure for the elderly through smarter and efficient tax administration.

Despite having one of the highest value-added tax (VAT) rates in Southeast Asia, the Philippines only collects about 40% of its potential VAT revenue. In 2018, for example, the government missed out on roughly P1.06 trillion, equivalent to 4% of GDP. Part of the problem lies in abuse and inefficiencies: fake PWD cards, numbering up to eight million despite only 1.8 million registered PWDs, result in around P88 billion in foregone revenues annually. Ghost receipts and fictitious VAT deductions are estimated to cost the country over P300 billion, or 1.2% of GDP.

To address this, we must broaden the tax base and review outdated exemptions. While politically sensitive, removing privileges that no longer serve their intended purpose can significantly boost revenues for social protection. A unified digital registry for all tax discount IDs — PWDs, senior citizens, solo parents — linked with the National ID system can help curb abuse. Expanding electronic invoicing and digitizing tax enforcement can reduce fraud and improve compliance. And as more commerce shifts online, capturing e-commerce transactions through smart regulation will help close the leakage gap while leveling the playing field.

When the economy fails to generate these opportunities, caring for the elderly becomes a private burden. Families are forced to fill the gaps. Resentment builds. Intergenerational conflict grows. Legislators respond with policies that politicize virtue rather than address structural problems. Children who earn well will naturally help their struggling parents, with or without a law that forces them to do so.

At the end of the day, genuine social protection rests on one thing: a working economy. When the economy grows, so does parents’ children and the State’s ability to provide care.

The choices are simple yet consequential: liberalize or let the gray wave crush us.

Given our policy trajectory, how are we faring? Right now, the answer is: not well enough.

Jam Magdaleno is a political and economic researcher, writer, and communication strategist. He is the head of Information and Communications of the Foundation for Economic Freedom (FEF), a Philippine-based think tank. Cesar Ilao III is a researcher and communications specialist for FEF. He was formerly a researcher at Monash University, Australia.