FERNANDO AMORSOLO was a beloved painter known for capturing what was perceived to be the essence of the Philippine identity, so much so that he became the country’s first-ever National Artist. At the Ayala Museum, his legacy as a “poet of color” and “painter of Philippine sunlight” is celebrated through a new exhibition that explores the viewer’s experience of the colors on his canvases.

Titled Amorsolo: Chroma, this rediscovery of the acclaimed artist’s famous works is curated by Tenten Mina. Notably, she places select pieces by Mr. Amorsolo’s contemporaries alongside his own, to better understand the art scene he moved in.

To encourage guests to engage with the art, the exhibition also includes a large interactive section featuring paint-by-color walls and digital stations which tackle color blindness. In a first for Philippine museums, EnChroma glasses are available for color blind visitors.

Ultimately, the exhibit dives into how Mr. Amorsolo’s use of light came to define a national aesthetic, and if it would still speak to viewers whose eyes may perceive certain colors differently.

REFRAMING WITH CONTEXTAprille Tijam, Ayala Museum’s assistant director and exhibitions and collection head, said that “younger viewers now comprise 40% of the museum’s visitors.”

“This exhibition seeks to reintroduce the works of Amorsolo to this new generation,” she explained during the exhibit’s launch in April. “It has been a decade since we last mounted a show dedicated to Amorsolo, and it is only fitting that we revisit how he shaped Filipino identity.”

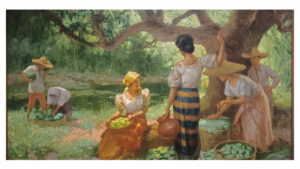

To illustrate his use of light and shade, they put together his pastoral landscapes, plein air paintings, and iconic genre works, many of which were “donated by overseas collectors who recognize the importance of bringing his art back home,” said Ms. Tijam.

Ms. Mina, the curator, gave a tour of the exhibit on opening day. She pointed out that, instead of doing a straightforward retrospective of the artist’s career, they focused on the early paintings of Mr. Amorsolo, spread out across “a series of interconnected alcoves, lit also to simulate natural sunlight.”

Visitors are naturally drawn to well-known works, like The Palay Maiden from 1920 and Planting Rice from 1924, but just as fascinating are quiet scenes of sunsets, sari-sari stores, fire trees, and multiple iterations of countryside maidens doing chores. Also memorable are folding screens containing plein air landscapes by both Mr. Amorsolo and one of his contemporaries, Juan Arellano.

“It was in the outdoors and painting in plein air that Philippine panorama and the golden sunlight that the artist found liberty. And remarkable are his small landscapes for their controlled, brisk, and spontaneous brushwork,” Ms. Mina said.

Despite featuring more of the smaller and intimate paintings of Mr. Amorsolo, the layout of the exhibit feels spacious, evoking a sense of the expanse of the outdoors present in the works themselves.

Though not a comprehensive overview of the artist, this part of the exhibit captures his formative years, placed alongside landscapes by predecessors and contemporaries — Jorge Pineda, Jose David, Isidro Ancheta, and even Mr. Amorsolo’s mentor and uncle, Fabian Dela Rosa.

“Context is important. We want visitors to ask themselves if stating that Amorsolo is the master of Philippine sunlight would resonate if also exposed to works of other landscape artists of that period,” explained Ms. Mina.

INTERACTING WITH EMPATHYThe second part of the exhibition is interactive and educational, with a “light room” that delves into the connection between art and technology, paint-by-color walls where visitors can contribute, and digital stations allowing us to view the warm glow of Mr. Amorsolo’s paintings from a color-blind perspective.

These aim to question “whether today’s audiences in the age of hypermedia and photo filters appreciate Amorsolo’s luminous legacy of colors in the same way.”

“One might argue that all exhibitions are experiential, and that all art is experiential. But what if I told you roughly 5% of Filipinos do not experience the full range of color? What happens to the claim that art is universal when color itself is not universal?” Ms. Mina said.

“Understanding that our assumptions about the human experience are not universal can be the starting point for empathy and dialogue,” she added.

The digital stations are eye-opening for those without color vision deficiency (CVD) or color blindness. Reduced sensitivity to greens and reds, for example, renders Mr. Amorsolo’s sunsets and landscapes a bit duller and more muted.

On the flip side, the EnChroma glasses offered to visitors with CVD allow them to experience Amorsolo paintings as intended.

For Ms. Tijam, this take on iconic paintings represents the Ayala Museum’s “ongoing commitment to accessibility and inclusion, particularly for persons with disabilities, assuring that as many people as possible can engage with Amorsolo’s work.”

Ms. Mina recommended that, coming from the interactive stations of the exhibit, visitors with regular vision go back to the first part, to gain a better appreciation of the colors.

“We want to encourage everyone to re-engage with the works and perhaps reassess if anything has changed their perception and appreciation of the displayed works,” she said.

Amorsolo: Chroma, which was made possible with the support of BPI and Boysen, runs until Sept. 7 at the Ayala Museum in Makati City. — Brontë H. Lacsamana